Diplomatic History Lessons: A Model of Government Transparency

With the Foreign Relations of the United States series, the State Department Office of the Historian provides policymakers and the public a thorough record of American foreign policy.

BY TRACY WHITTINGTON

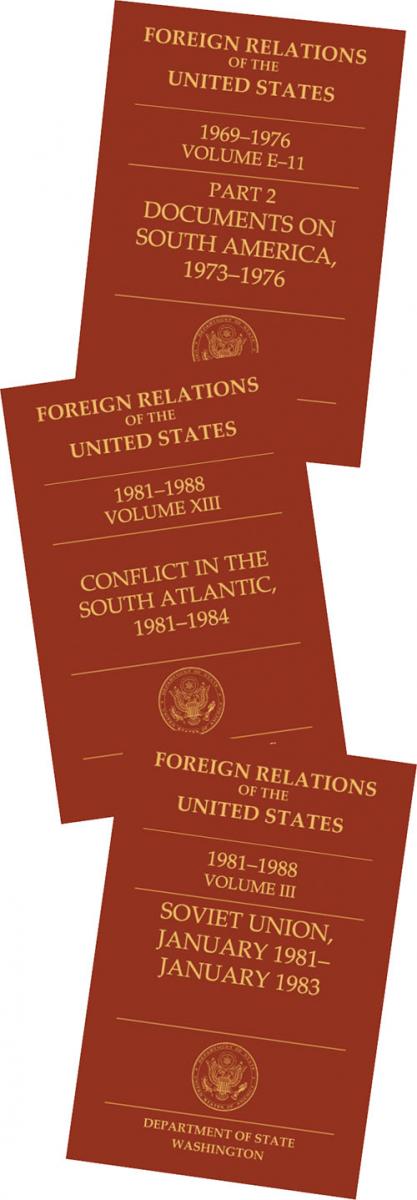

In a restored Navy hospital dormitory on the hill across from the Harry S Truman building more than 40 Ph.D. historians are at work on the largest and most productive documentary history program in the world. They and their predecessors stretching back to 1861 have compiled 562 volumes of the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) series, providing half a million pages of declassified government documents to Congress, scholars and the general public.

Today the Historian’s Office serves vital policymaking needs within the department, providing just-in-time history to bureaus and officers around the world, in addition to making available to the broader public a treasure-trove of declassified documents and historical diplomatic information of record in the form of the FRUS volumes, as well as extensive digital resources at the office’s website, history.state.gov.

The office’s mandate is significant: to provide a “thorough, accurate, reliable” official record of U.S. foreign policy. Although many countries have some process for documenting government foreign policy decisions, the FRUS program is the gold standard—the oldest, most comprehensive and most formalized. Indeed, FRUS provides a model of responsible government transparency and accessibility that has endured through more than 150 years of political change, hot and cold wars, and not infrequent institutional or partisan efforts to interfere with it.

Policy Accountability: A Brief History

Decades before the Bureau of Public Affairs and the Bureau of Legislative Affairs were a twinkling in the eye of the Secretary of State, the department’s annual bound submission to Congress of the previous year’s foreign policy documents fulfilled both bureaus’ missions. As per its constitutional obligation (Article II, Section 3), the country’s executive branch informed the legislative branch of its foreign policy actions.

FRUS also informed the general public. Until the early 1900s, newspapers from the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin to The New York Times covered this release to Congress of contemporary sensitive diplomatic cables, department instructions to the field and even documents originating from foreign governments. Congressional and public reaction was mostly positive; it turned out those ambassadors actually knew what they were doing.

Budget cuts, followed by the outbreak of World War I, eroded the timeliness of the series. By 1930, FRUS had settled into a 15-year publication lag and become a mechanism of historical, not immediate, accountability. Later attempts to bring the volumes back to currency were eclipsed by post-World War II changes in Washington’s foreign policymaking machine and the birth of the interagency. Today’s FRUS volumes are more heavily weighted toward documentation of the decision-making process than the back-and-forth between Washington and posts.

Department of State documents that once made up 90 percent of the material in FRUS fell to less than 30 percent by the Nixon and Ford administrations, with the addition of White House, National Security Council, Defense, Treasury and other U.S. government agency records. At the same time, the inclusion of intelligence information whenever necessary introduced inevitable but lengthy delays as governmental declassification apparatuses struggled to accommodate the regularized release of once highly sensitive material.

In the 1980s, a battle royal developed within the State Department between parties in favor of expanded transparency and those inclined to keep the foreign policy sausage making hidden from public view as long as possible, if not forever.

Indeed, in the 1980s, a battle royal developed within the State Department between parties in favor of expanded transparency and those inclined to keep the foreign policy sausage making hidden from public view as long as possible, if not forever. Transparency won the day with the 1991 FRUS statute, signed by President George H.W. Bush, which forced the department to facilitate Historian’s Office access to classified documents and systematically declassify records at the 30-year mark (or justify withholding them).

This tug-of-war over the publication of our official history produced the mostly collegial atmosphere in which FRUS is compiled today. A State Department and Central Intelligence Agency joint historian facilitates searches of the CIA’s historical records and greases the declassification machine by serving as a thoroughly vetted intermediary. Relations are also good with the external FRUS governing body, the Historical Advisory Committee. Founded in 1957 and statutorily mandated since 1991, this body of academic and public-interest representatives monitors the progress of the series.

The HAC has lobbied on behalf of FRUS, protesting to Congress when its members believed the series did not meet transparency standards—as with the “incomplete and misleading” Iran, 1951-1954 volume—and advocating more timely release, as when the series fell nearly 40 years behind in the 1990s. (A fascinating account of the series’ history produced by the office of the Historian’s special projects division, Toward “Thorough, Objective, and Reliable”: A History of the Foreign Relations of the United States Series, received the prestigious Society for History in the Federal Government’s Pendleton Prize for 2016. It is available at history.state.gov.)

The Making of a FRUS

So what’s it like to be a FRUS historian? The general consensus: like a kid in a candy store. With access to the universe of primary source governmental documents and immersion in the particular period now under study—the 1970s and 1980s—FRUS historians can claim the greatest expertise on U.S. policymaking during these decades of anyone in the world. No serious book on U.S. foreign policy is published without FRUS footnotes, and few outside historians have the pride—or responsibility—of knowing the books the president and Secretary of State have on their nightstands are based in large measure on the documents they have compiled. In addition, the globe-spanning nature of U.S. foreign relations renders FRUS as much a record of world history as American history. For citizens of some countries, particularly those whose governments have yet to, or will never, publicly share their own documentation, the work of FRUS historians offers their only window into their own nations’ foreign policies.

Since the 1990s, FRUS has been organized chronologically by presidential administration. The Historian’s Office begins its work on each administration with a thorough reading of memoirs and the extant secondary literature of the period, as well as extensive review of the documentation at the relevant presidential library. Editors create a list of probable topics, ranging from traditional bilateral foreign policy and crises (e.g., Berlin Crisis, 1961-1962) to themes such as foreign economic policy and national security policy. Most one-term presidential administrations require 25-30 volumes; most two-termers, 45-50.

With the 19th century’s nation state–centric foreign policy increasingly giving way to extranational concerns, volumes on global issues have multiplied. Early “general” chapters on international concerns, like the protection of fur seals in the Bering Sea, have become volumes on, for example, the United Nations. Often, global issues volumes have anticipated the creation of functional bureaus to address those issues. Recent proposed or in-progress Reagan-era global issues volumes will be devoted to immigration and refugees and the war on drugs and terrorism.

The historian working on a particular volume has two years to read, conduct research at multiple venues in and outside of the beltway, and select and annotate the 1,400 document pages (out of an almost infinite number possible) to become the 800-900 pages of a published FRUS volume. And that’s just the first step. The manuscript then goes through a five-month review process with two readers, followed by six weeks of revision by the historian. Then, the entire timeline moves out of the hands of the Historian’s Office when they submit the documents for declassification.

The Historian’s Office has also released several “retro” volumes that revisit sensitive episodes in our diplomatic history that earlier FRUS editions covered poorly due to limited access, stymied declassification or political interference.

On average, this takes two additional years, but delays of up to six years are not uncommon. (While the Carter administration volumes have nearly all been released, and the first two Reagan volumes, Conflict in the South Atlantic, 1981-1984, and Soviet Union, January 1981–January 1983, were published recently, three volumes from the Nixon-Ford era still await full declassification.) After this hurdle, editing and publishing the volume takes another year. The average span between policy and publication is 35 years, with 30 the goal. Since the early 1980s, when only one or two volumes were released annually, publication rates have snowballed. In just the last two years, 19 volumes have come out.

In addition, the Historian’s Office has released several “retro” volumes that revisit sensitive episodes in our diplomatic history that earlier FRUS editions covered poorly due to limited access, stymied declassification or political interference. In 2013 the Historian’s Office published Congo, 1960-1968, containing records related to the death of Patrice Lumumba. This followed a retro volume on Guatemala, 1952-1954; another retro volume, Iran, 1951-1954, is still in production. New perspectives on the importance of previously underappreciated areas of policymaking can also inspire retro volumes, as with the FRUS, 1917-1972, Public Diplomacy multimedia volume.

The Historian’s Office has also undertaken the digitization of the FRUS series, creating a free, online, full-text searchable archive on the office’s website: history.state.gov. So far 260, or more than half of the 500 or so volumes in the series, can be browsed online or downloaded as e-books; and within three years, the entire series from its inception in 1861 will be online, through an exchange with the University of Wisconsin.

More broadly, the office uses the website to advance its twin goals of increasing transparency and accessibility. For example, the website is secure, ensuring that pages visited by its readers, including overseas readers who constitute 25 percent of the site’s traffic, cannot be tracked. An update of the website currently underway will make it faster and easier to browse on mobile devices, whose users are a rapidly growing proportion of the site’s visitors. In addition, both the website and e-books are accessible by individuals with visual disabilities who use screen reader software. Further, as part of the Open Government Initiative, all source code and raw data underlying the site are freely downloadable, empowering researchers to do more advanced work—including textual analysis and data visualization.

Just-In-Time History: Analysis for Policymakers

While FRUS garners most of the publicity, and represents the lion’s share of the office’s work, the historians also serve State’s immediate needs. Since 1944, the policy studies and special projects branches of the Historian’s Office have undertaken more than 2,500 policy studies of varying lengths, supporting current and future policymaking in the department. (The public website, mentioned above, includes not only FRUS content, but draws on many of these studies to provide institutional history and other policy material.)

A decade ago, historians with regional portfolios established an ambassadorial briefing program to bring the lessons of diplomatic history to new Foreign Service officers as part of the A-100 orientation curriculum. The Historian’s Office also has a longstanding oral history program that aims to build historical repositories on key foreign policy events, such as the Arab Spring uprisings and the 2014 Afghan elections crisis, before the documents are lost and participants’ firsthand recollections fade. Central to it all is the guidance provided to policymakers at State and in the broader national security community on events and issues of the most recent three decades.

Occasional history emergencies notwithstanding (new Secretaries of State have called on the office for studies of their predecessors’ initial months on the job or the role of special envoys and representatives), the need for historical analysis is not limited to the top of the organizational chart. Most weeks find the office providing just-in-time history to bureaus and officers from all corners of HST and the globe. On one recent warm spring day the historians were at work on these requests:

• The National Security Council called with a query on visits by foreign leaders, drawing on information continually updated by a staff historian who also maintains a compilation of the travels of the president and secretary and of all principal officers and chiefs of mission.

• A FRUS historian with expertise in Western Europe put the finishing touches on “A Historical Study of the ‘Special Relationship’ Between the United States and the United Kingdom,” while other geographic experts worked on bureau-solicited papers ranging from “Leaving Mogadishu: U.S. Policy toward Somalia in 1990” and “The Reagan Administration’s Strategy to Counter Soviet Disinformation, September–October 1983.”

• To move a major project combing oral and documentary history forward, a two-person team mined old files on Israeli-Palestinian negotiations for a history of the Middle East peace process under George W. Bush.

• Preparing for a session with the incoming A-100 class, a historian supplemented the 1938 Vienna consular simulation exercise—How would you have implemented department guidance aimed at stemming the tide of would-be immigrants in pre-WWII Austria?—with material related to later refugee outflows from the Balkans, the Great Lakes (Africa) and the Middle East.

• The office provided advice to an inquiring deputy chief of mission about identifying possible records of historical value related to the Ebola crisis and how to work with Administration Bureau records managers to preserve them.

• In addition to requests for policy research, the historian staffing the history@state.gov mailbox fielded short-term micro-taskers from the Secretary’s speechwriters, consulates and embassies, academics and journalists, in addition to responding to a sixth-grader hoping the Historian’s Office could email his questions to Henry Kissinger.

Tapping the Mother Lode

Why is it so important to know about State’s Historian’s Office? For current foreign affairs practitioners, it offers valuable historical background. Few offices have an employee who can remember, for example, the most contentious issues in a round of United Nations negotiations 10 years ago; fewer still have the time or resources to gather this critical information before the next round starts. For researchers at all levels and in all locations, FRUS provides a mother lode of declassified government documents that would otherwise require a trip to a federal depository library, as well as historical diplomatic information of record through history.state.gov.

And for the American people, the Historian’s Office delivers one of the benefits of responsible, democratic government: the transparency needed to interpret the past in support of informed policy decisions today.

Read More...

- Office of the Historian, Historical Documents (Department of State)

- Foreign Relations of the United States (University of Wisconsin-Madison Digital Libraries)