2025 Posthumous Awards for Dissent

Myles Standish (front row second from right) and Hiram Bingham (front row left) with consular staff in Marseilles.

Courtesy of Scoti Woolery-Price

Posthumous Awards for Dissent

Honoring Moral Courage in the Face of Injustice

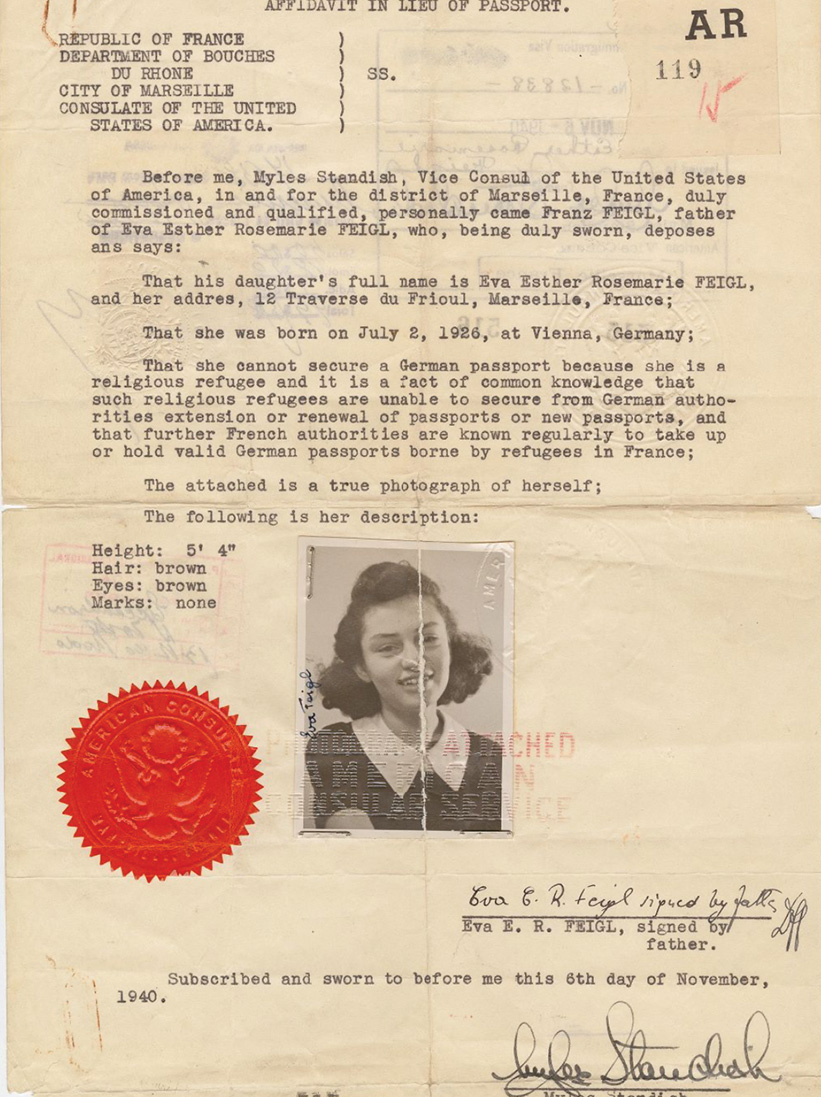

Affidavit for Eva Feigl signed by Myles Standish.

Courtesy of Scoti Woolery-Price

This year AFSA is honoring 12 U.S. career diplomats whose moral courage during the Holocaust exemplified the highest ideals of constructive dissent. Working individually under extraordinary pressure, and often at great personal risk, these men stood against indifference and bureaucratic paralysis to save lives, resist persecution of others, and uphold humanitarian principles.

AFSA created this special Posthumous Dissent recognition to honor Foreign Service members whose actions met the bar for constructive dissent, choosing duty to humanitarian principle when policy fell short. The nominations came from historian Eric Saul, who first approached AFSA years ago with extensive research and later submitted specific cases that clearly evidenced dissent. This year’s honorees follow in the path of Hiram “Harry” Bingham IV, whom AFSA recognized in 2002 for similar rescue efforts during the Holocaust.

In Moscow and later in Ankara, Ambassador Laurence Steinhardt (1892-1950) used every diplomatic and personal resource available to him to save lives. One of America’s most experienced envoys, Steinhardt served in Sweden, Peru, the Soviet Union, Türkiye, Czechoslovakia, and Canada. While posted to Moscow and Ankara during the height of Nazi persecution, he worked with the War Refugee Board, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, and the Vatican’s Monsignor Angelo Roncalli (later Pope John XXIII) to coordinate the rescue and transit of thousands of Jews from Eastern Europe. His correspondence and instructions to his staff reflected a deliberate choice to use diplomacy as a tool of compassion, even when official channels offered little guidance or support.

From the U.S. consulate in Tangier, Rives Childs (1887-1987) risked his career to save more than 1,200 Jews fleeing Vichy and Nazi persecution. A veteran of World War I and a seasoned Foreign Service officer, Childs persuaded Spanish authorities to issue transit visas and established safe houses for Jewish families until Allied forces reached North Africa. He worked quietly with Renée Reichmann of the Joint Distribution Committee to coordinate relief under the cover of diplomatic activity, defying strict limitations on immigration and refugee assistance.

Few U.S. diplomats confronted the Nazi regime as directly as Raymond Geist (1885-1955), who served as U.S. consul general in Berlin. Geist intervened personally with German officials to secure the release of Jews from concentration camps and ensured that every available U.S. visa under the German quota was issued between 1938 and 1939. His office became a refuge for desperate families seeking a path to safety, and his insistence that Germany’s visa allotment not be redistributed to other posts resulted in thousands of lives saved. Geist’s tenure in Berlin stands as one of the most consequential examples of principled action within the constraints of prewar U.S. immigration policy.

In Switzerland, Ambassador Leland Harrison (1883-1951) turned his position into a lifeline for victims of persecution. A career diplomat with postings in Sweden, Romania, and Switzerland, Harrison relayed early reports of Nazi atrocities to Washington, supporting Gerhardt Riegner’s detailed accounts of mass killings. Despite bureaucratic resistance in the State Department, he championed the efforts of relief agencies, including the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the International Red Cross, and facilitated communication between the War Refugee Board and Jewish organizations operating in Europe. His dispatches from Bern helped ensure that the full scope of Nazi crimes reached Allied policymakers.

Ambassador Herschel Johnson (1894-1966), U.S. minister to Sweden from 1941 to 1946, likewise refused to let virtuous action be muted by overly cautious diplomatic policy. In Stockholm, he pressed Washington to take more active measures to protect Jewish refugees, reported on Swedish rescue operations for Danish and Norwegian Jews, and worked to build public and political support for humanitarian action. Johnson’s recommendation that the War Refugee Board send Raoul Wallenberg to Budapest as Sweden’s special envoy would ultimately save tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews; Wallenberg himself issued protective passports and sheltered Jews in buildings he declared Swedish territory before he was detained by the Soviets and disappeared.

Working in Geneva as the War Refugee Board’s representative, Roswell McClelland (1914-1995) became one of the central figures in the Allied relief effort. A former Red Cross representative, McClelland managed $10 million in aid for humanitarian operations across occupied Europe, channeling funds to support Jewish refugees and coordinate relief convoys. His collaboration with Swiss, Vatican, and neutral diplomats provided critical escape routes and shelter for children who otherwise would have perished. Though his work was largely unheralded during his lifetime, McClelland’s reports offer an extraordinary record of determination, empathy, and effective dissent through action.

Among the earliest to sound the alarm about Hitler’s rise, George Messersmith (1883-1960) used his position as U.S. consul general in Berlin to chronicle, in vivid terms, the Nazi regime’s escalating brutality. He issued warnings to Washington as early as 1933, condemned Nazi abuses in a series of detailed memoranda, and advocated strongly for a more forceful American response following the November 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom. Messersmith’s moral vision and staunch criticism of appeasement made him one of the most outspoken figures in the Foreign Service during the interwar period.

World War II refugees lined up at the U.S. consulate in Marseilles in 1941.

Courtesy of Scoti Woolery-Price

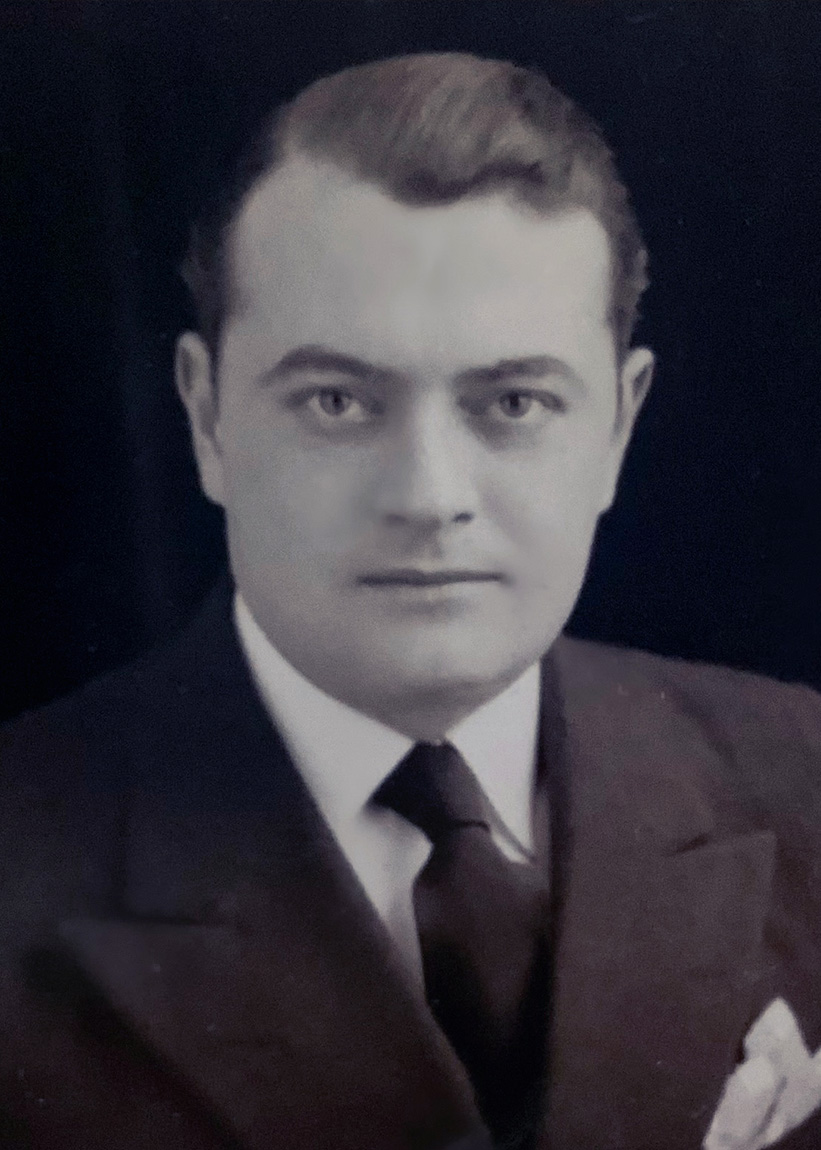

Myles Standish in the early 1940s.

Courtesy of Scoti Woolery-Price

Paul Squire (1903-1972), serving as U.S. consul in Bern, became the crucial link between the European resistance and Washington when he transmitted the now-historic Riegner Telegram in August 1942. The cable conveyed the first reliable intelligence of Hitler’s plan to exterminate Europe’s Jews. Squire’s insistence on verifying and forwarding the report, despite skepticism in Washington, ensured that the evidence reached policymakers and Jewish organizations abroad. His persistence helped force the issue of genocide into the official record at a time when denial and disbelief were widespread.

In southern France, Vice Consul Myles Standish (1909-1979) carried out one of the most daring acts of diplomatic humanitarianism of the war. Stationed in Marseille from 1937 to 1941, he worked closely with the Emergency Rescue Committee and the American Friends Service Committee to secure exit visas, travel documents, and transport for Jewish and political refugees. Among those he aided were artist Marc Chagall and writer Lion Feuchtwanger. Defying restrictive immigration quotas and orders to cease such activities, Standish personally escorted refugees to the border and organized clandestine departures. Later, he worked for the War Refugee Board, where he was responsible for developing escape routes. He organized escapes from the Axis-held territory for political and religious refugees behind enemy lines. He was particularly active in the efforts to rescue abandoned children. He also compiled the first U.S. government list of war criminals.

Envoy Myron Taylor (1874-1959) brought to his role as President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s personal representative to the Vatican a keen sense of moral leadership. A prominent businessman before becoming involved in diplomatic efforts during World War II at the request of Roosevelt, Taylor used his influence to confront Nazi atrocities directly with Pope Pius XII. His memoranda and private appeals urged the Vatican to take a public stand on deportations, and his advocacy contributed to papal statements condemning racial persecution. Taylor’s mission helped keep international attention focused on the plight of Europe’s Jews during the darkest years of the war.

As chargé d’affaires in Vichy France, Pinkney Tuck (1896-1993) confronted French Prime Minister Pierre Laval to protest the deportation of Jewish children and petitioned Washington to grant them U.S. entry. Tuck’s dispatches revealed the human toll of the collaborationist regime and pressed for a stronger American response. His persistent advocacy led to the rescue of hundreds of refugees and earned him wide admiration among humanitarian and diplomatic circles after the war.

Finally, George Waller (1892-1962), U.S. chargé d’affaires in Luxembourg, used his limited authority to great effect. When Nazi occupation engulfed the country, Waller expedited visas and travel documents for Jewish families desperate to flee. His quick action and willingness to bend restrictive rules enabled numerous escapes from the advancing German army. For his humanitarian service, Waller was later awarded the Luxembourg War Cross; the military decoration was created by Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg on April 17, 1945, to recognize extraordinary feats of military service and bravery.

Working individually, often without support or against the wishes of the U.S. government, these 12 diplomats transformed the instruments of diplomacy—visas, cables, and reports—into instruments of conscience. In standing against indifference and fear, they affirmed that dissent, when guided by humanity and principle, is not disloyalty but devotion to the moral core of U.S. service. Their example continues to guide the U.S. Foreign Service today, reminding us that quiet courage can change the course of history.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.