Like Lightning from a Clear Sky: Watching Guerrillas Recruit in Peru

To assess extremist non-state actors, you have to risk taking a “dance with the devil.”

BY STEPHEN G. MCFARLAND

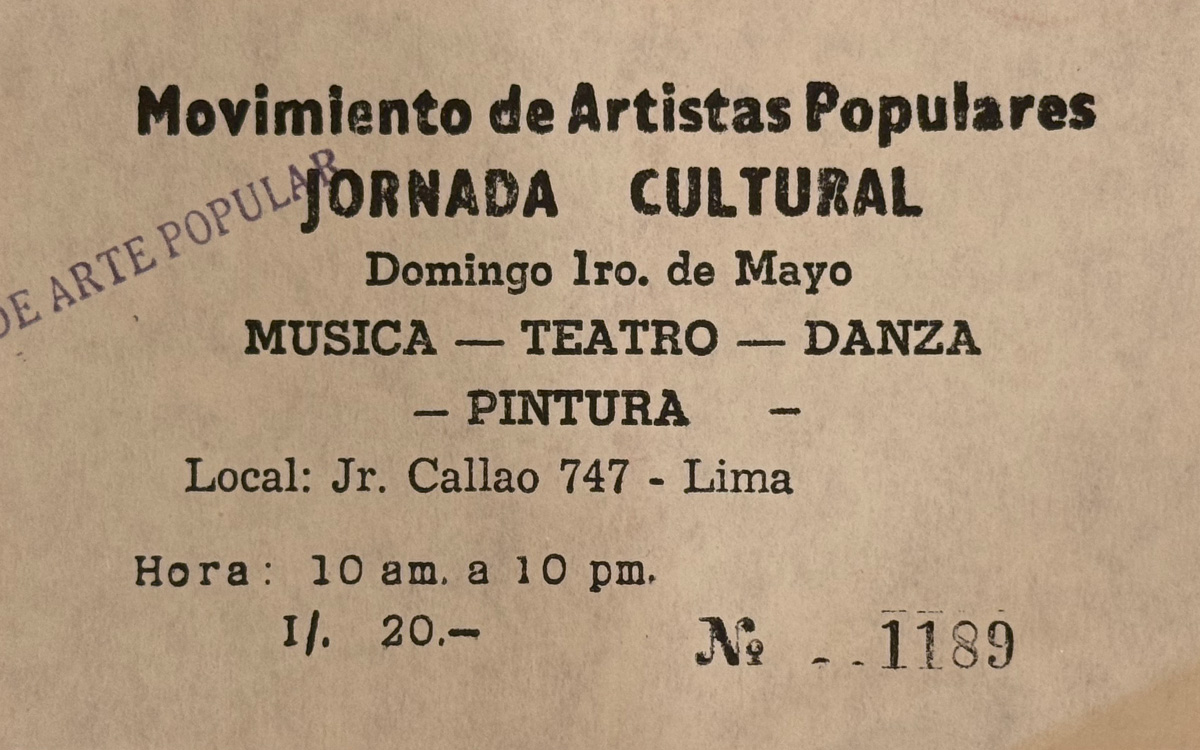

Path’s Recruitment event on International Workers’ Day, May 1, 1988, in Lima.

Courtesy of Stephen McFarland

You cannot defeat an enemy you do not understand.

Peru’s elites had underestimated the Sendero Luminoso (“Shining Path”) guerrillas’ capabilities, intentions, motivation, and appeal. By 1988 the country was eight years into war with the Shining Path. More than 40,000 persons had died in this conflict that struck “like lightning from a clear sky,” historian Alberto Flores Galindo wrote, taking by surprise the Peruvian government, the private sector, academics, and the gamut of political parties. In 1980 a democratically elected president, Fernando Belaunde, had returned to power after a leftist military coup 12 years earlier. Marxist parties, some of which had supported the military government, had abandoned calls for rebellion and instead contested the elections.

The Shining Path, however, had done the opposite. Based in Huamanga University in the mountain town of Ayacucho, it was led by the charismatic philosophy professor Abimael Guzmán. A Maoist who had visited China during the Cultural Revolution, Guzmán made that version of Maoism his template for crushing the Peruvian state and installing a “People’s Republic of New Democracy.” The Shining Path’s terrorism spread outward from the mountains of south-central Peru, and the group had expanded attacks in Lima, seeking the war’s tipping point.

I was the embassy political officer reporting on the armed conflict. And, concerned about its impact on the drug trade and stability, the Washington interagency wanted more. Peru was one of the two top producers of coca leaf for the cocaine trade, and the Shining Path had started to protect traffickers and coca farmers against the government. Terrorism, including attacks against U.S. facilities, put a brake on foreign investments and fueled worries about Peru’s democracy.

I traveled in the Shining Path heartland, solo and without appointments, in and out. Some contacts shared not only their experiences, but also clandestine documents and captured guerrilla notebooks. A bullet hole had perforated one of these notebooks. I never learned the backstory, but it symbolized the stakes of political violence. What drove people to join it? With more initiative than caution, I went to a recruitment event to find out.

§

§

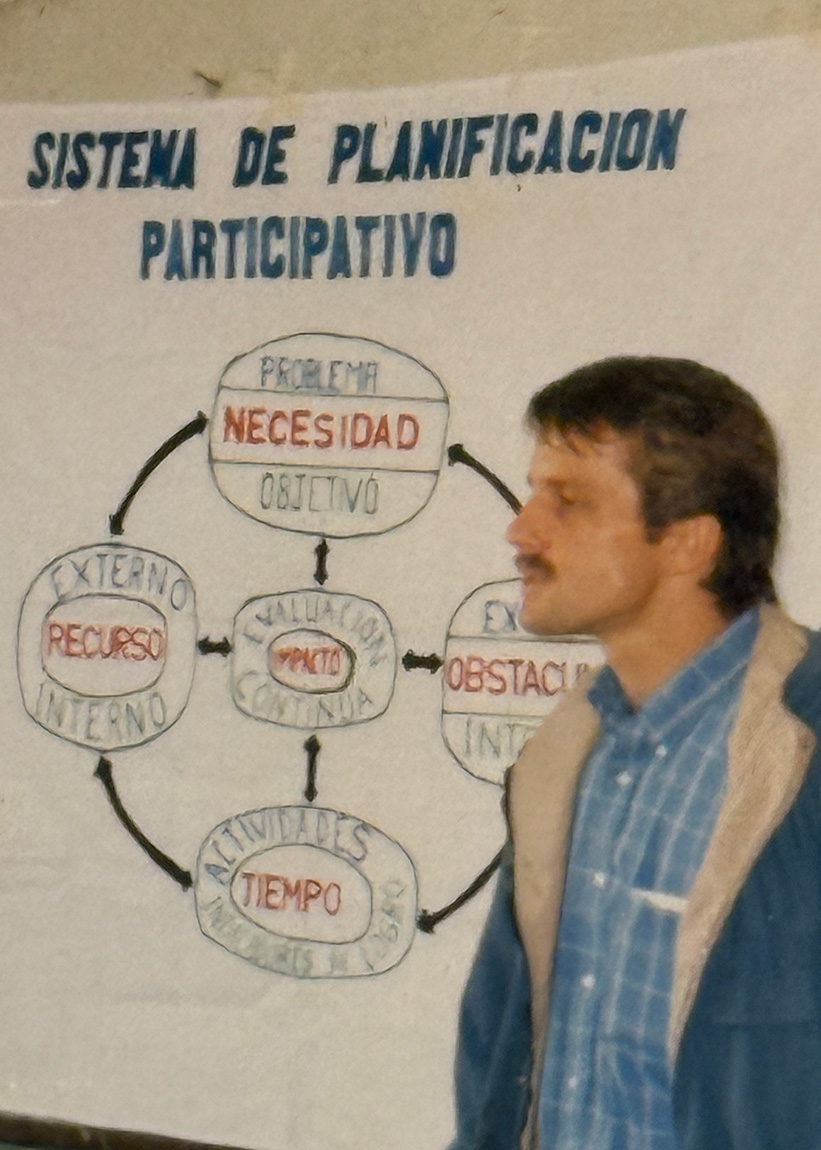

The author, in 1988, speaking at a meeting hosted by a local foundation with Quechua-speaking farmers outside the town of Quinua in Ayacucho department. Quinua experienced considerable violence during the conflict, and the farmers opposed Shining Path.

Courtesy of Stephen McFarland

I entered the rundown building in downtown Lima, only a mile from the U.S. embassy, and walked down a dark and narrow corridor. The occasion was the Shining Path’s recruitment and propaganda event for International Workers’ Day on May 1, 1988, and more than 200 people had already arrived. I wore gray jeans and a weathered windbreaker that did not scream “foreigner.” The Shining Path considered the United States an enemy, so I tried not to look suspicious, no easy feat as one of the whiter and taller persons in the crowd. I spoke native Spanish, and I carried only a regular passport; if challenged, I was a tourist. Nobody stared at me. The only exit was where I had entered, and I kept an eye on it for three hours.

As the May Day event kicked off, red flags bearing the yellow hammer and sickle papered the wall, marking this as the Shining Path’s turf. The people around me were mostly men, but about a quarter of the crowd were women. They ranged from teenagers to people in their 40s, with most in their 20s and 30s. Most were mestizo—i.e., they had a mixture of Indigenous and white ancestors—but about a third appeared more Indigenous. How could a radical and cruel Maoist insurgency inspire such interest despite a counterinsurgency campaign marked by executions, disappearances, and torture? Something didn’t add up.

The Shining Path had organized the international workers’ day event through its Popular Artists’ Movement and advertised it through its still-legal newspaper. Both front groups provided political and information support and reportedly supported attacks. The organizers’ hook for the audience was a simple, impassioned explanation why Peruvians outside the elite had no hope of improvement. In the face of Peru’s unforgiving hyperinflation and its political system’s indifference, the Shining Path told people their lives could have meaning by fighting for a higher cause and standing on the winning side of history, even at the risk of capture, torture, and death. They read poems, performed dramatic skits about revolutionary violence, and praised party leader Guzmán, referred to as “President Gonzalo.”

A puppet show portrayed a Shining Path cell’s execution of a mayor—including a depiction of the authorities’ subsequent capture and torture of the perpetrators. Then someone read a poem by one of the more than 300 “martyrs” who had died in the Shining Path’s 1986 prison uprising: “Poetry is not just a flower, pretty and beautiful, but also a machinegun that gives birth like a star.” Another poem emphasized the role of women: “I saw you, Carmela, light the dynamite’s fuse …”

The last presentation was the re-enactment of a Chinese Communist Party play about the Chinese Revolution. A group of peasants, suffering exploitation and starvation, join the Communist Party and embrace the armed struggle; they overthrow and execute their cruel landlord. The transformed peasants then raise their rifles and the Party’s red banner toward the sky. The folks around me cheered.

When the slogans stopped, we broke ranks, and I chose that moment to leave while I was ahead.

Next it was the audience’s turn. A Shining Path member shouted an order, and attendees lined up by rank and file—it was the first time I’d done so since my military training. We were instructed to sing the “Internationale,” the 19th-century Marxist and socialist anthem. The organizers ran out of copies of the lyrics, so I could only repeat the chorus and lip sync as I tried to blend in.

Then came the climax. As the singing ended, a young Shining Path woman belted out slogans, repeated by other members and even some of the attendees around me: “Long live Marxism-Leninism-Maoism-Gonzalo thought!”; “Down with the dictatorship!”; “Long live President Gonzalo!”; “Long live the people’s revolution!”—and multiple times, “Long live the armed struggle!” Clearly some attendees had found something they could believe in. Their lives now had a purpose.

When the slogans stopped, we broke ranks, and I chose that moment to leave while I was ahead. I slipped into the dark corridor and walked out unnoticed. After hours of Shining Path rhetoric, the adrenaline rush of being outside was invigorating. Thus, my encounter with the would-be Shining Path members was concluded, or maybe not.

Some of those recruits may well have subsequently surveilled us or attacked our contacts or the embassy. When I returned to Peru in 1992, perhaps some of the newer captured guerrilla notebooks I read had belonged to them.

§

§

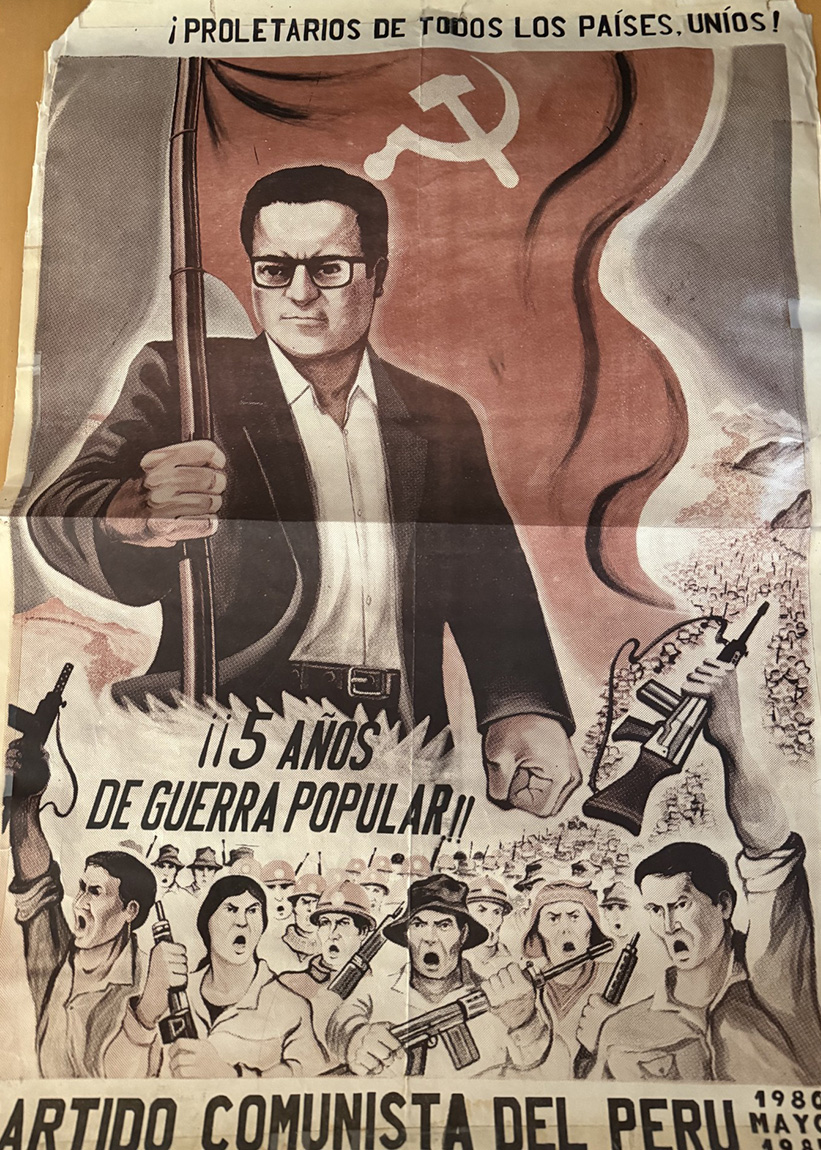

This Shining Path poster from 1985 highlights the “armed struggle” and illustrates the “cult of personality” surrounding Shining Path leader Abimael Guzmán.

Courtesy of Stephen McFarland

A critical metric for violent extremists is their ability to grow and replace members who are killed or captured. Al-Qaida in Iraq, and later the Islamic State, ultimately failed to do this in Iraq, but the Taliban succeeded in Afghanistan. The Shining Path sought quality in its recruits; the alleged members I had met in the mountains showed motivation, obedience, and what Shining Path ideologues called “class consciousness”—including a willingness to die for the cause, what their leaders termed “crossing the river of blood.”

In the Ayacucho countryside the Shining Path had grown through the university’s contacts with students and villagers. As the war’s intensity increased, Shining Path violence against peasants reduced its appeal, but military human rights violations helped the guerrillas to recruit. Outside Ayacucho, a peasant told me that while no one in his community supported the Shining Path, the soldiers had still killed his brother; what he was most worried about, however, was the soldiers’ theft of his sheep, his family’s livelihood.

The Shining Path’s ideology based on class warfare found fertile ground in a Peru whose stark inequalities tracked major racial, ethnic, class, and regional divisions, and resentment. Many at the May Day event were likely from families that had migrated from the mountains to the capital’s shantytowns. They appeared to be mostly from the lower class, with some from the lower-middle class, but not from the very poor. Many looked like, and probably were, workers in dead-end jobs in the informal economy, or state university students, or low-paid government employees who struggled under hyperinflation. Clearly the Shining Path’s urban recruiting base was much broader than the government or the U.S. embassy imagined.

Peru’s politicians dismissed the Shining Path as lacking popular support, and it is true that it would have lost in an election. But that missed the point: Shining Path’s leader was building an elite, hierarchical, and ideologically pure Maoist party to use organized violence and, in particular, terrorism to seize power. As in Russia in 1917—and later elsewhere, from the left and the right—a resolute, ruthless extremist minority could conquer a larger but disorganized majority. The Shining Path had begun the war in 1980 with about 200 members and, even at its apogee, had at most 10,000 to 20,000 members, compared to a Peruvian military and police force that exceeded 100,000 and a much larger civilian government apparatus.

The Shining Path relied on violence, including the engagements it lost, to build support. Members justified terrorism and the selective assassination of real or perceived opponents, armed and unarmed. Their methods were crude, but as I reflected in 1993 while retrieving pieces of an engine block from the car bomb that had exploded outside my Embassy Lima office, crude methods can work.

The group’s emphatic but flawed analysis of Peru’s systemic inequality and injustice, if accepted by recruits, led to the “logical” next step of justifying revolutionary violence to conduct systemic change. In George Orwell’s 1984, the protagonist Winston Smith observed that the Party could order citizens to believe that “two plus two equals five.” The Shining Path stoked the resentment among non-white Peruvians over racial, regional, and class-based exclusion to shape it into the class-based violence Mao had championed.

The Shining Path’s Marxist competitors looked down on them as unschooled cousins from the country (reflecting more than a little racism, classism, and big-city snobbery on their part). But the pro-Soviet communists were behind the times, the Trotskyites were irrelevant, the traditional pro-China parties were uninspiring, and the new pro-Cuban Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement that sought to emulate Central American guerrilla groups was ineffective. The legal leftist parties challenged Sendero in the towns, often paying with their lives, but they were hopelessly divided at the national level.

Under the circumstances, Peruvian elites had assumed, wrongly, that the large enough use of indiscriminate military force would defeat Shining Path; instead, it had the opposite effect. As the United States had learned in Vietnam and in El Salvador, and would relearn the hard way in Iraq and Afghanistan, a military can kill real or suspected guerrillas, and civilians, in such a way that motivates even more persons to join the guerrillas.

In 1989, facing failure, Peru’s military changed its doctrine to treat civilians less as enemies, and more like potential allies, and expanded armed self-defense groups, or rondas, in the villages to fight Sendero. The police changed too. Police officers I met in 1988 had proposed a more intelligence-based effort. And in 1990 the Peruvian police formed a special counterterrorism group that used legal investigative techniques. Two years later, with alleged U.S. support (according to American journalist Charles Lane and former police officers in this unit), the counterterrorism group captured Sendero head Guzmán and his senior leaders without firing a shot.

The leadership’s decapitation led to Shining Path’s collapse. Almost no new Sendero leaders emerged, and recruitment was near zero.

Shining Path propaganda on the walls of a school outside Huancayo in the central Andes in February 1988, as the Shining Path stepped up its presence there.

Stephen McFarland

The United States has also struggled, and sometimes failed, to comprehend extremists, terrorists, guerrillas, and insurgents. In Iraq and Afghanistan, our tactical intelligence often identified enemy capabilities and even intentions, but we lacked sufficient understanding of insurgent motivation, recruitment, and support. Success requires understanding why otherwise normal individuals join an effort that they know they may not survive and how people, per Orwell’s observation, can believe that two plus two equals five.

One reason foreign (and local) observers misjudge foreign internal conflicts is that having lived in societies that have functioned relatively fairly and effectively, we fail to appreciate the resentment generated by societies that are systemically less fair and effective, more discriminatory, divided, and sometimes even predatory. “Clientitis”—excessive confidence in host country governments and elites’ strategy and understanding of their country—was another huge obstacle for the United States in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere.

We gloss over critical factors that are hard to measure, such as people’s desire for justice, for understanding why they always remain on the bottom, for belonging to something bigger than themselves, and even why they might relish the companionship born of the shared risk of clandestine activities. We have excessive confidence that a globalized, democratic, private sector–led economic model will self-correct toward stability and social justice.

To overcome these challenges, foreign and local observers must get outside the middle- and upper-class enclaves, open their eyes, and employ vigilant empathy—at times, an armed empathy—to understand the causes and drivers of extremism. U.S. Foreign Service officers, our diplomats, are in a unique position to understand the capabilities and intentions of non-state actors, including extremist and violent groups. Doing this, outside the diplomatic bubble, requires taking calculated risks based on experience, analysis, tradecraft, and intuition. We also rely on the role of luck, even if we don’t know how much.

Not every risk is worth taking; not every dance with the devil ends well. But the reward is unique insights that boost our ability to pursue our objectives in a dangerous world.

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.

Read More...

- Diplomacy Works Part II, The Foreign Service Journal, January-February 2018

- “The FRONT-Line Initiative: Combating Transnational Criminal Organizations” by Christopher “Kai” Fornes, The Foreign Service Journal, October 2018

- “Right of Boom: A Bomb and a Book” by Stepehen G. McFarland, The Foreign Service Journal, September 2021