Logrolling in Rural Thailand

Reflections

BY DICK VIRDEN

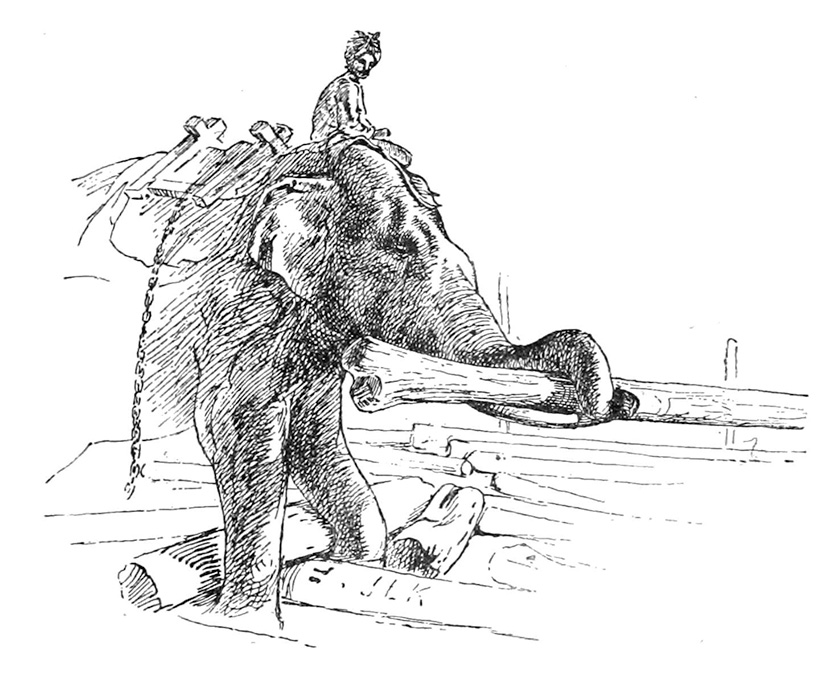

A drawing of an elephant lifting teak logs in Southeast Asia as appeared in The Popular Science Monthly.

Wikimedia Commons

Uttaradit is a changwat (province) in north central Thailand. One day late in 1968, some Thai companions and I found ourselves literally spinning our wheels there, stranded on a remote, hilly trail. This is the story of why we were there and how we got out of our fix.

Our trip was part of what in those days was called counterinsurgency, or the battle for hearts and minds. As the United States Information Service (USIS) representative based in the adjacent province of Phitsanulok, I was charged with organizing field information programs to villages in the five provinces of a north central region bordering Laos and Burma.

As a first assignment, it did not exactly fit the pattern for a fledgling diplomat. One of my Foreign Service classmates dubbed me “Lord Jim,” from Joseph Conrad’s book by that title; upcountry Thailand must have looked rather exotic from his European vantage point. But, in fact, I was no unique, lone-wolf adventurer. At that time, USIS had a dozen branch posts making similar expeditions to the country’s 50,000 or so villages.

On this day, we were heading for a group of villages due to be displaced by the Queen Sirikit Dam, which was being built to provide flood control, irrigation, and power to the surrounding area on the Nan River.

Our goal was noble: try to ensure that villagers knew what was afoot and convince them that they would benefit in the long run. There was good reason to suspect little had been done to inform or try to influence them, since reaching out to people in rural areas was alien to Thailand’s authoritarian tradition.

The overarching concern was that disaffected villagers might be tempted to join the ranks of communist insurgents threatening the government in Bangkok, an important U.S. ally in the war then raging nearby in Vietnam and Laos (and soon enough in Cambodia as well).

Despite our lofty purpose, our mobile information team (MIT) and the Jeep CJ-6s that carried us were stymied by a prosaic problem: A huge tree had fallen across the only trail available.

We were a group of about a dozen, counting my two Thai assistants and officials—as usual, an assortment of vets, teachers, health workers, and administrators—from the province and district. But with that log squarely in our path, we had no way to proceed, no direction home, as my fellow Minnesotan Bob Dylan wrote.

The answer was not blowing in the wind, but it was at hand in the surrounding teak forest. Someone remembered that elephants were the go-to means of logging thereabouts. Maybe we could track down a crew and persuade them to help us out?

And so we did. The details of our search and rescue are a bit murky—it’s been more than half a century!—but eventually we did find some elephants at work and convinced a handler to take on the offending log. As I recall, said elephant made short work of the challenge.

Path cleared, we were able to move on to a string of villages, some of which had rarely seen their government up close or considered that it was there for them.

For a couple of nights, our team provided information, services, and even entertainment (we showed films, stringing sheets between bamboo poles and using our portable generator since the villages lacked electricity).

The villagers seemed pleased enough, though it would be a stretch to claim—much less try to prove—that hearts were moved or minds changed.

Later I would submit my favorite petty cash voucher ever: “100 baht ($5). Rental of elephant to remove log from trail.”

It was reimbursed too.

Also, the dam was completed and is still functioning today.

And, of course, Thailand never did “go communist.” But that’s another tale...

When sharing or linking to FSJ articles online, which we welcome and encourage, please be sure to cite the magazine (The Foreign Service Journal) and the month and year of publication. Please check the permissions page for further details.